Of Victorian Monsters and Ghoulish Men: A (Brief) History of Halloween

Written by Erin Benedictson

Halloween in the 21st century summons up images of a cool fall evening, trick-or-treaters travelling from door to door in search of sugary confections, and spooky costumes that range from superheroes, to princesses, to villains from classic slasher movies. Despite feeling decidedly modern, Halloween has a centuries-long history, running all the way back to its origins of Samhain with the Celts, and reaching peak eeriness during the Victorian era and their obsessions with death.

The Celtic people, who once populated the area of the world we now mostly know as the British Isles, are the ones who originated the autumn festival known as Samhain. During the time of year marking the end of summer and harvest, welcoming in the harsh winter, it was believed that the boundary between the living and the dead was at its thinnest. Unlike the Día de los Muertos holiday celebrated in Mexico, which is considered to be a happy celebration of ancestors, Samhain’s activities focused mainly on banishing otherworldly spirits that roamed into the world of the living and caused damage to crops. However, the presence of spirits was met with mixed feelings – the presence of them made it easier for Druids to make predictions about the future, which was often a comfort during the long, dark winter. It is during Samhain that costumes first started to make their appearance, although they more likely wore animal skins and heads rather than the traditional Halloween images of witches, black cats, and spooky ghosts.

Jump forward a few thousand years, and we find ourselves deep in the Victorian era, where most of our modern-day traditions of “spookiness” find their origins. The obsession with death that the Victorians held began with the untimely death of Prince Albert, the husband of Queen Victoria. Albert’s death welcomed in a strict tradition of rules and regulations regarding how Victorians must mourn their deceased loved ones in the public eye. The mourning period was often years long and included entire new wardrobes consisting solely of black clothing and jewellery, and restrictions on what kind of public activities they were allowed to partake in. Anything that strayed from society’s expectations of how one must mourn could make you a social and moral failure. While well outside the ordinary customs, Queen Victoria herself followed intense rules of mourning, including wearing black for the rest of her life, and apparently freezing her home in time, insisting the servants continue to lay out her husband’s clothing and change his bedsheets, as if he had never died.

Queen Victoria and her family in mourning, with a bust of Prince Albert | Photo by John Jabez Edwin Mayall | 1863 | Courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust

The Victorian era dates from 1837, when Alexandrina Victoria, to be known as Queen Victoria, ascended the throne at the age of 18. It would last until her death in 1901, making her the second-longest reigning monarch in British history. (Lougheed House was built in 1891, at the tail end of the era, and boasts many Victorian style choices in its design and architecture.) The era was rife with notions of change in all arrays of society. Innovations in science and technology were at their height, while the adoption of germ theory contributed to the rise of modern medicine. High mortality rates in the early to mid-Victorian period were contributed to by the intense growth rate of towns and cities, along with a lack of understanding of how health and safety fit into burgeoning technology.

A newspaper ad for mourning attire | c. 1860

With death’s constant presence, Victorians used it as inspiration to explore the idea of spirits, a “good death”, and predictions of their futures. A “good death” for the Victorian involved a set of practices that required painstaking detail and often, small fortunes. A particular emphasis was made on the state of the souls of the deceased. A fear was that after one died, their spirit or soul would haunt or possess the living, whether good or evil, and many precautions were made to ensure they would be lead elsewhere, preferably out of the house they died in. Mirrors were covered to prevent the trapping of the soul in the reflection, and family portraits were flipped to prevent the spirit from possessing the living. Clocks were stopped at the time of death to honour the moment, avoid bad luck, and allow the deceased to continue on. After being laid in the ground, clocks would restart again. The colour black, made popular by their monarch, symbolized the absence of light and, ultimately, life. For those more superstitious, it also was believed to hide the mourning from the deceased and prevent them from haunting. Many superstitions also involved the unconscious life of dreamers, with many dream interpretations leading to an omen of death or predictions of bad luck.

Newspaper ad for Peter Robinson’s Family Mourning Warehouse, advertising to families of all classes | c. 1900

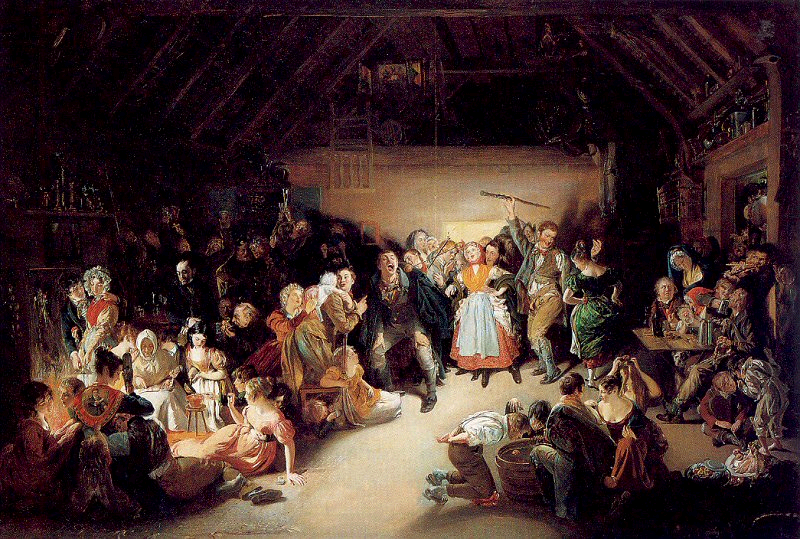

Despite these macabre associations, Halloween was still considered to be a celebration for most people during this period. While décor and mourning traditions were more of a ghastly and ghoulish nature, parties and gatherings were more upbeat and positive. Activities and games were often about predictions of the future, much like the Celts, especially focusing on one’s romantic future. Rather than sweets and bonbons, food consumed during All Hallow’s Eve was more often nuts and fruits, such as roasted walnuts and glazed apples. One particular Halloween tradition that originates in Ireland is the barmbrack cake, although we are more likely to know it as a traditional fruitcake. Hidden inside the cake were five different tokens: a ring, a penny, a thimble, a button, and a key. Guests would eat slices of the cake in the hopes they would find one of the tokens, and thus predict their future, courtesy of the token they discovered. A ring signified marriage, a penny wealth, the thimble would solidify your lifelong status as a bachelor or maid, a button signifies finding a sweetheart, and a key would indicate a journey. A person dedicated as “Dame Halloween” would slice and serve the cake, while utmost silence would be held, lest any stray predictions of the future be told. If anyone uttered a single word during this process, which they often did, prophecies could be told of the future based upon what was said. The future was similarly predicted during Halloween parlour games, such as cracking walnuts and the game of the Three Luggies, while others were simply for entertainment, such as blind man’s bluff, pin the tail on the donkey, bobbing for apples, or the rather ominously cheerful-sounding Wink Murder.

Looking into a mirror to see one’s future husband was a popular Halloween game in the Victoria era | Artist Unknown

Between the ancient festival of Samhain to today’s sugar-infested festivities, autumnal gatherings of a spooky nature have always been popular. Familiar threads weave throughout the centuries, with ghosts and spirits remaining constant companions during this time of year, and the obsession with the dead and its rituals reaching a peak in the Victorian era. Even today, Victorian superstitions around death still linger in part, such as holding your breath when going past a graveyard, or the belief that death comes in threes. While we may no longer have rules around official mourning customs, black is still a sign of grief. We still love to tell ghost stories of monsters and other horrid creatures. The fascination has never diminished, and celebrations today still very much resemble those of the past. The spirit of Halloween is here to stay, lingering like the spirits did on those cold, Celtic winter nights.

Halloween

Upon that night, when fairies light

On Cassilis Downan dance,

Or owre the lays, in splendid blaze,

On sprightly coursers prance;

Or for Colean the rout is ta’en,

Beneath the moon’s pale beams;

There, up the Cove, to stray an’ rove,

Amang the rocks and streams

—Robert Burns

We respect your privacy as per our Privacy Statement. We welcome your thoughtful and respectful comments, and your first name will appear with each submission. All comments will be moderated by Lougheed House before they appear on the site. We check for posts regularly and will respond as soon as we can. We do not guarantee that your comments will be published.

By submitting a comment, you accept that Lougheed House has the right to reproduce and publish that comment in whole or in part, in any form we choose. We do not endorse the opinions expressed in comments. Comments on this page are moderated according to our Submission Guidelines. Comments are welcome while open. We reserve the right to close comments at any time.