An Ugly Truth: Digging Through History to Understand the Present

Written by Harpreet Dhanjal, member of our Community Advisory Committee for Lougheed House Re-Imagined.

May 7, 2008. It was yet another beautiful morning in a string of beautiful mornings – which was apparently quite odd, so said the locals. We boarded a bus from O’Connell Street in Dublin, Ireland, and headed to Glasnevin Cemetery for a tour. Just another part of our itinerary. Our guide talked about all the usual suspects, all the men we’d already been learning about and seen statues of, men that played an important role in Irish independence. But then the tour took a turn. Our guide stopped at the headstone of Elizabeth O’Farrell. None of us had heard of her; as it turns out, not many people had. She was an important part of the Easter Rebellion, and as we would come to learn throughout the course of the trip, there were many women who played crucial roles in the history of Irish independence. Where were their statues, the streets named after them, books and writings about their triumphs? They’d essentially been erased from history.

Irish Nurse and Cumann na mBan member Elizabeth O’Farrell | c. 1910s | Unknown Photographer | Glasnevin Cemetery Museum

History is written by the victors, our guide pointed out. No one talks about the women, because men were the ones writing history. It was these words that made me question everything I’d learned through Social Studies and history classes, and rethink how I’d examined and viewed history to this point. Throughout this trip I began to realize that I’d always heard one dominant narrative of historical events. I took that narrative as fact and I filed it away. I never actually dug deeper, explored any of the hidden histories that were behind the stories, never critically examined or questioned what I was hearing. Why would I? It was in a history book, a textbook, in a museum. People more knowledgeable than me were telling me this is how it was. It was during this trip I realized that I’d reached adulthood with a very shallow understanding of history; there is a whole other world to explore beneath the surface.

Easter Rising Surrender, 1916. Elizabeth O’Farrell is standing behind the man on the right, but only her shoes and skirts are visible. In some reproductions of the photo, her presence has been erased entirely. | April 29, 1916 | Unknown Photographer | National Photographic Archive

The trouble is, things get tricky when you start digging. It’s easier to repeat the glossy, rose-coloured glasses version of history because it’s comfortable. When you start peeling back the layers and actually begin exploring, things can get very uncomfortable, very quickly. When you start digging into our own country’s past, you realize that Canadian history is not pretty. Nor are the stories associated with some of the celebrated figures of its history. We’ve just done a really good job of hiding those ugly parts and wrapping them up in pretty packaging.

“Alright,” I hear some people say, “Alright, fine, history isn’t pretty, some bad stuff happened – but that’s in the past, let’s just move on. Why do we need to keep going back to it?” Well, friend, it’s because until we understand history and examine it honestly with all its ugly parts, we can’t actually understand the ripple effects of that history and how it still impacts the world we live in. The structures, the institutions, the inequities that are in place today, are a legacy of that past.

April 2014. It was a pretty typical Calgary classroom where I gave my students an assignment to explore the question, “Was Sir John A. Macdonald a good leader?” As part of their assignment they had to decide if the answer was yes, or no, and provide me with at least three arguments to support their stance, along with at least two arguments that went against that stance. Why was this important? I needed them to understand how to make strong arguments, to critically examine a topic and find evidence to support their theories, while also evaluating alternative perspectives. Macdonald was a whole human being with many aspects to his identity, many of them quite ugly – specifically his view of Indigenous communities. What effect did that have on the choices he made, the policies he enacted, the people he surrounded himself with? How did that play into what kind of a leader he was? Could he be considered a good leader to some and not others? Why? The discussion these questions created was important, and what at first appeared to be a simple yes or no question became more complicated the more they dug in.

Sir John A. Macdonald and the British High Commissioners for the Treaty of Washington | 1871 | Matthew B. Brady | Library and Archives Canada, C-002422

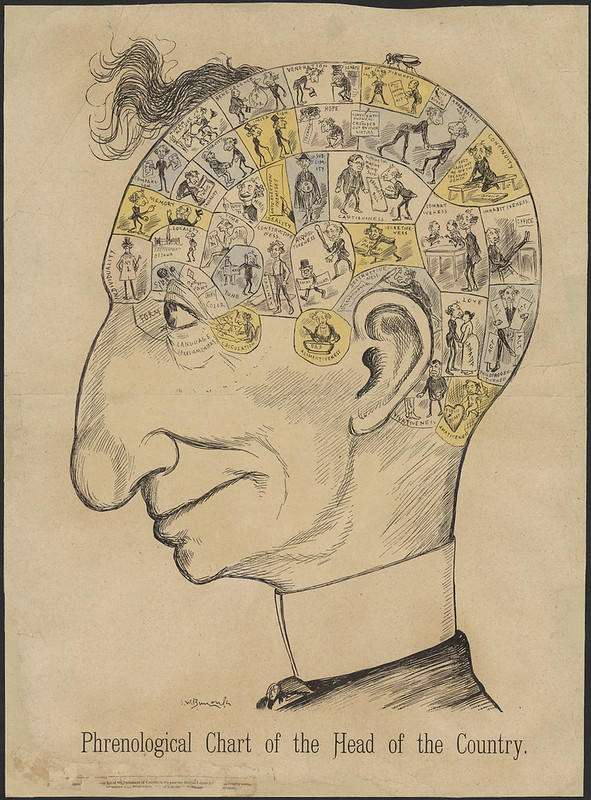

Caricature portrait by Sir John A. Macdonald’s “favourite” critic | 1887 | J.W. Bengough | Library and Archives Canada, e010930930

April 2000. I found myself in a grand banquet room at the Palliser Hotel in downtown Calgary. I couldn’t remember ever having been in a place so fancy; eating a meal that was so intimidating I was afraid of making the wrong cutlery decisions. Female leaders and other young female students from around Calgary were in the room with me and I was perplexed as to why my teacher had asked me to attend this event. Then the keynote speaker started speaking. She talked about a group of women – The Famous Five, she called them – and instantly I was captivated, listening to a story of these trailblazing women who paved the way for all of us in that room to be strong, independent women ourselves. She talked about as women how much we owed them, and I was buying this beautiful tale she was selling of these amazing women that deserved all our reverence. It wasn’t until years later I realized my initial discomfort, sitting in a fancy room, with fancy place settings, surrounded by predominately white women wasn’t misplaced: those five women, the Persons Case – that story wasn’t for me. Years later when I dug deeper, I discovered the very complex and ugly realities behind the women who made up The Famous Five. This included openly racist ideologies and support of eugenics. What is the legacy that this has left? Can we talk about the good while ignoring the bad? Who was erased from history so that this narrative could be presented? Why, when talking about Emily Murphy and Nellie McClung, for example, don’t we also talk about the Sexual Sterilization Act? This isn’t to say we shouldn’t celebrate the wins The Famous Five gained for some women, but we cannot continue to ignore the social and political context around them, what it meant to the ones they excluded, and the ripple effect that created.

Nellie McClung of the Famous Five | September 20, 2020 | Calgary, Alberta | Ted McGrath, Flickr

Famous Five memorial | January 20, 2018 | Calgary, Alberta | JMacPherson, Flickr

Asking these questions is not easy, but it’s 2021 – look at the state of the world around us. It’s time to get uncomfortable. Because unless we lean into that discomfort and begin examining history critically and honestly, we have little hope of effecting positive change for a better and more equitable future. And who knows, maybe you’ll uncover some beautiful truths in the process.

Author of this post, Harpreet Dhanjal. Photo credit Calvin D’Silva.

Harpreet Dhanjal (she/her) is a Community Engagement Specialist at the University of Calgary. She has a background in research, education, and program development. Representation, diversity, and equity are a big part of her own practice and something she cares deeply about. In her free time, she’s an avid baker and enjoys creative projects such as cake decorating and quilting.

We respect your privacy as per our Privacy Statement. We welcome your thoughtful and respectful comments, and your first name will appear with each submission. All comments will be moderated by Lougheed House before they appear on the site. We check for posts regularly and will respond as soon as we can. We do not guarantee that your comments will be published.

By submitting a comment, you accept that Lougheed House has the right to reproduce and publish that comment in whole or in part, in any form we choose. We do not endorse the opinions expressed in comments. Comments on this page are moderated according to our Submission Guidelines. Comments are welcome while open. We reserve the right to close comments at any time.

Yes Preet! I loved this. I love how you put your own stories in there because it made me reflect on my own experiences too. I think about this a lot because I’ve always been fascinated by history but am only realizing in the last 5-10 years how the stories are skewed. At first I feel guilty but then I realize that as a youth I put so much trust in my teachers that I just accepted everything in the textbooks as fact. It was only in my later years of university that I started to question my teachers and textbooks. I’m excited for the changes we will hopefully see in museums, textbooks, tours, etc. when people like you ask question and dig deeper.