This Land is Whose Land?

Written by Kay Burns

As a Canadian born of immigrant parents, I have mindlessly gone about my daily living from a position of privilege and naïve ignorance when it comes to understanding how settlers can own land here in this expansive continent. Throughout my education within the Canadian school system that delivered one-sided colonial viewpoints, through constant exposure to societal biases reflected in all aspects of white-privileged culture, I never thought to ask many important questions until the past couple of decades. Through purposeful and incremental unearthing of perspectives that are different from those that informed my youth, I continually seek to broaden my understanding.

Within the position of Exhibit Coordinator for Lougheed House Re-Imagined, part of my role has been to look for the alternative stories, the surprising stories, and the hidden stories. Something that surfaced for me is how James Lougheed acquired the land on which he built his businesses and home. Every step of that exploration goes further and further back, essentially highlighting the peculiarity of colonial acts over centuries that ultimately led to James Lougheed’s ability to acquire land, and to the continued growth of this city within what is now known as western Canada.

One of the early acts that led to the “ownership” of western Canada occurred when England’s King Charles II granted a Royal Charter in 1670 that permitted his cousin, Prince Rupert, the right to establish a fur trading business. The name of the charter was The Governor and Company of Adventurers trading into the Hudson’s Bay; in other words, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC). The king essentially gave his friends and family a monopoly over the commercial exploitation and development of resources in the new world.[1] This established Britain’s legal exclusive possession and prevented any other would-be colonizers from laying a claim to the region now known as Rupert’s Land. The parameters of this region eventually included all land with rivers and waterways that fed Hudson’s Bay; it “extended from Labrador to the Pacific, from the Pacific Northwest to the Arctic Ocean, an area approximating one twelfth of the Earth’s land mass.”[2]

The vast area of land that the charter claimed was already inhabited by numerous Indigenous communities. This clearly was not a deterrent from a colonizer’s perspective:

“[King] Charles understood that he couldn’t take land that didn’t belong to him. But he retained an idea of land ownership for Europeans, ignoring the territory’s Indigenous inhabitants. Within the HBC charter, Charles outlined whose land he would not claim: “that of British subjects, or ‘the Subjects of any other Christian Prince or State.’ In other words, any other European power.”[3]

While British officials may have considered the effects of this charter an extraordinary achievement for how “British commerce could transform — or ‘civilize’ — the globe,”[4] it most dramatically, from today’s perspective, highlights the sheer hubris, arrogance, and entitlement of Imperial colonizers.

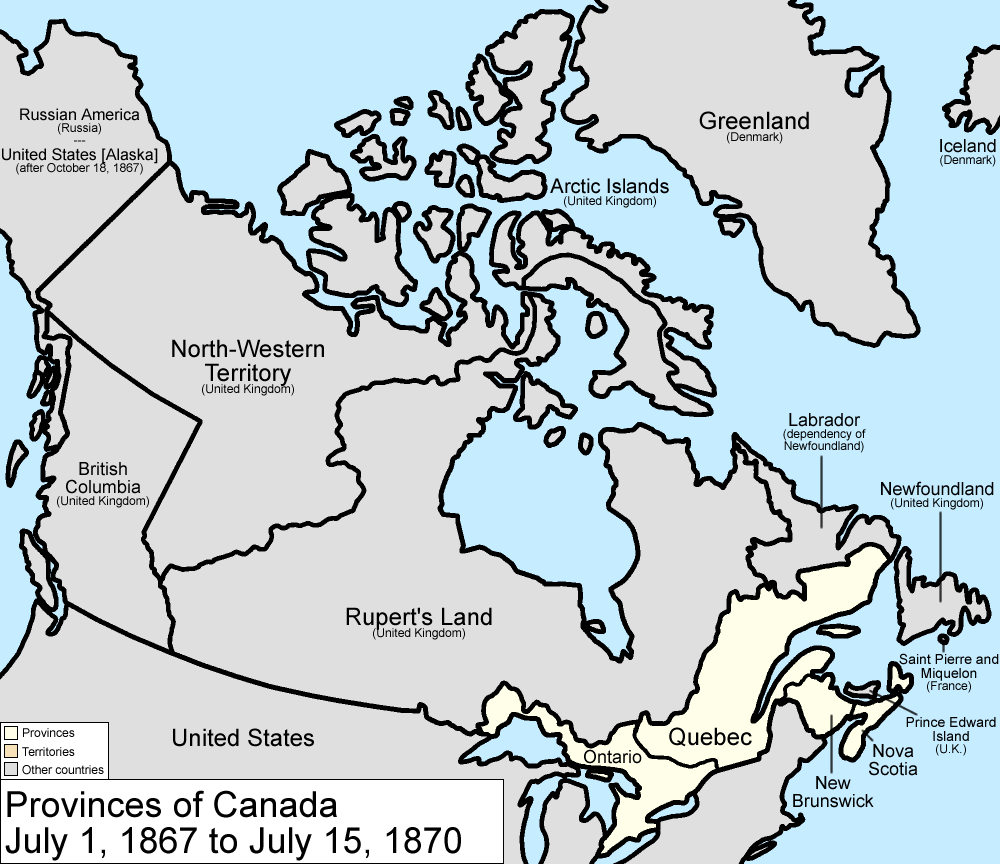

Canadian provinces in 1867 after Confederation

In 1870, the HBC sold this ill-gotten land claim to the Dominion of Canada (3 years after confederation) for £300,000 (approx. $1.5 million),[5] which radically transformed the geography of Canada from a modest country into an expansive region from coast to coast, joining with the western Colony of British Columbia.[6] In 1867 when the Dominion of Canada was formed, it included the southern portions of Ontario and Québec plus New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. By annexing Rupert’s Land into the Dominion, Prime Minister Sir John A Macdonald was able to expand the new country’s boundaries dramatically. And the governors of HBC were content to comply with a transfer of land ownership.

“HBC was… tired of colonial administration. Though the Company was instructed by the British government to promote settlement, this was fundamentally at odds with the interests of the fur trade. As colonial settlers arrived, the forested areas that provided habitat for the fur-bearing animals were cleared. As long as the fur trade was to be the Company’s primary focus, settlement would never garner wide support among its shareholders or staff.”[7]

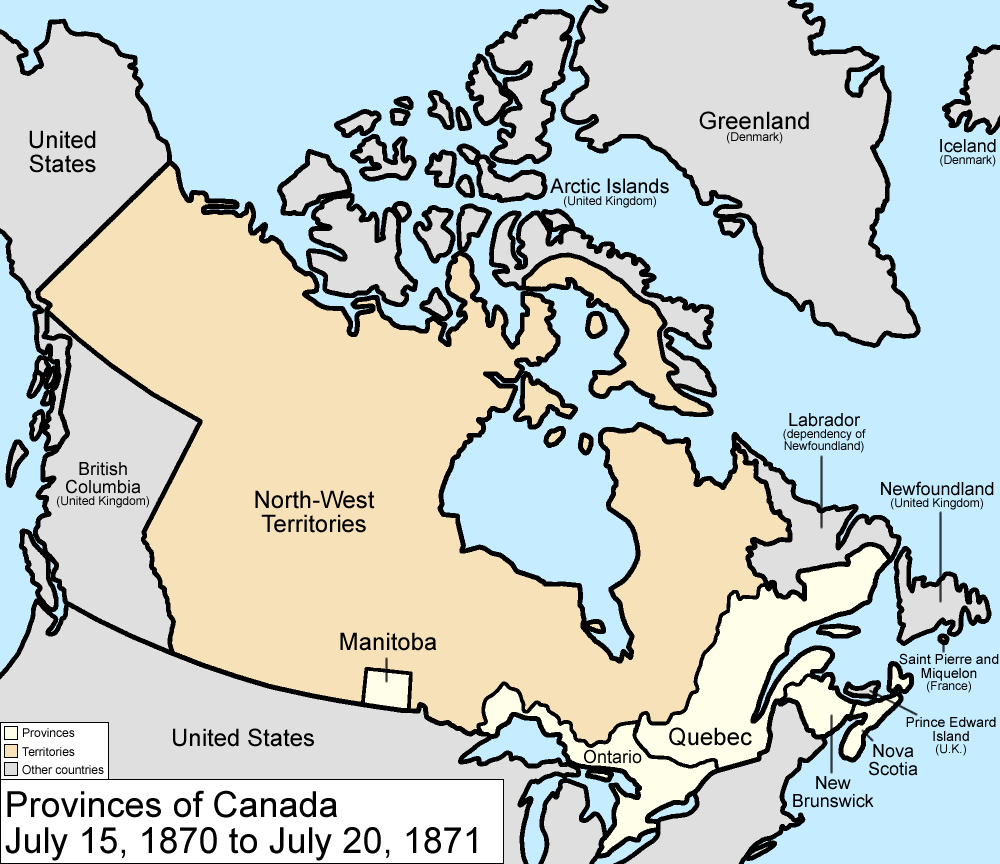

Canadian Provinces from 1870-1871

The transfer of Rupert’s Land, however, was certainly not met with appreciation by all (even though the colonizers were delighted to take ownership). The land transfer led to the Red River Resistance. The Métis at Red River did not recognize the HBC as having control over the territory, and therefore viewed the land transfer as illegitimate.

With the Government of Canada now in control of Rupert’s Land, now known as the Northwest Territories, colonizing strategies were implemented to bring in settlers and farmers from eastern Canada and Britain/Europe to populate the west. The Dominion Lands Act was the legal mechanism implemented in 1872 which allowed for parcels of land to be granted to individuals, colonization companies (corporations designed to promote and co-ordinate immigration and settlement), municipalities, and religious groups.

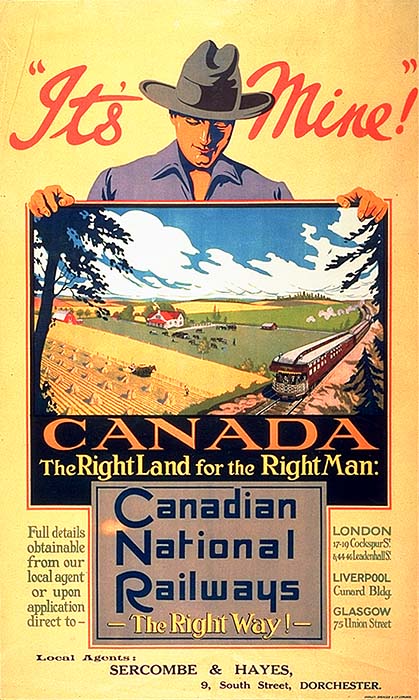

Immigration to Canada poster | Canadian National Railways | n.d.

Part of the Dominion Lands Act included setting aside land for First Nations reserves and Métis lands.[8] Given that First Nations did not consider land as something that could be bought and sold, the concept of land ownership shifted dramatically. The model went from a concept of shared occupation with those already present, to an entitlement enforced by those who moved in. The government was bound by the terms of the 1763 Royal Proclamation, which made Canada responsible for the protection of its Indigenous peoples. [9] Within it, the king claimed ultimate authority over the territory, and he prohibited any individual person purchasing land from Indigenous groups, which was a right he reserved for himself and his heirs. “This established the constitutional basis for the future negotiation of Indigenous treaties in British North America. It made the British Crown an essential agent in the transfer of Indigenous lands to colonial settlers.”[10]

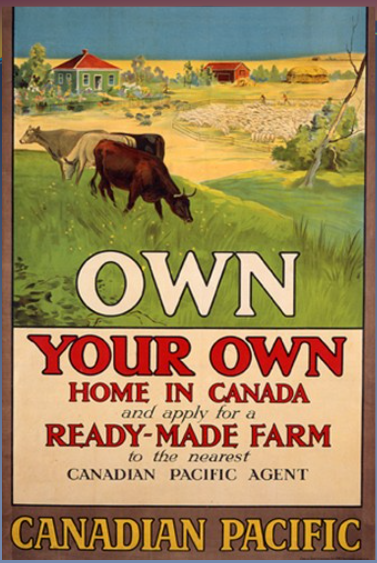

To more easily facilitate colonization activities, the Government of Canada provided land and access to the Canadian Pacific Railway company to build a transcontinental rail line. The CPR was granted millions of acres of land either side of the railway right-of-way. This was the most desirable land across the prairies, as rail access was imperative to settlement and new industries. The CPR were shrewd business operators; they not only provided passenger and freight transport by train, but they also had a fleet of ships, and were now landowners. They sought to encourage and facilitate the arrival of immigrants (primarily from eastern Canada and Britain). [11] They devised a package to sell to immigrants that included passage on a CP ship, travel on a CP train, and land that was purchased from CPR holdings. “The owners of the CPR knew that not only were they creating a nation, but also a source of economy for their company.”[12]

Immigration to Canada poster | Canadian Pacific | n.d.

Clearly a connection to the CPR was advantageous. James Lougheed, a young lawyer from Ontario, essentially followed the route of the railway as it was being built, until he reached Calgary in 1883, where he remained. CPR became one of his most important clients. His legal practice primarily dealt with real estate and transportation law. He also invested heavily in real estate himself and opened a brokerage firm. The timing of his arrival in Calgary, his connections to the CPR, his advantageous marriage to Isabella Hardisty with significant family connections to the HBC, all contributed to James’ increasing wealth and capacity for finding the right land opportunities.

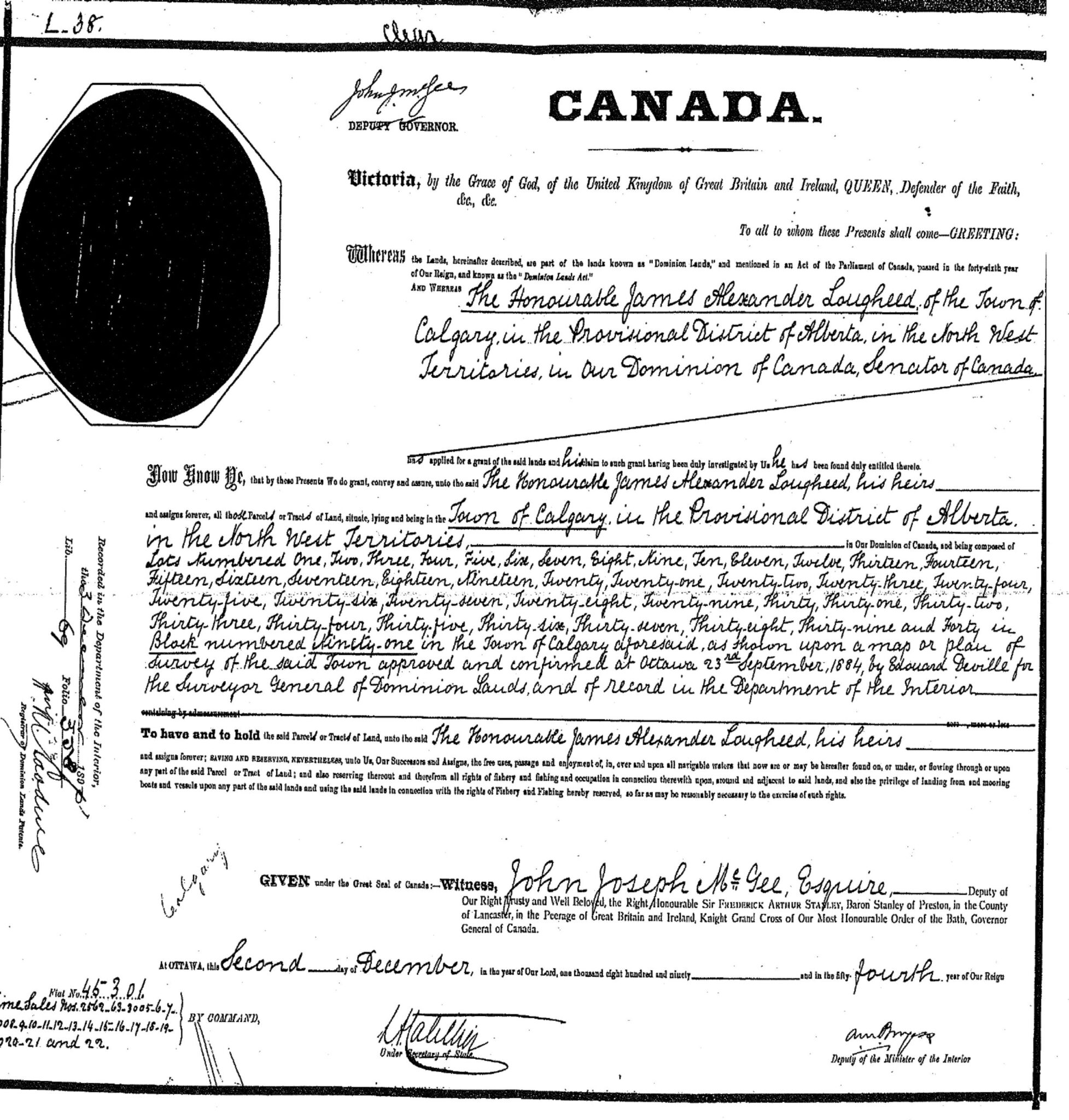

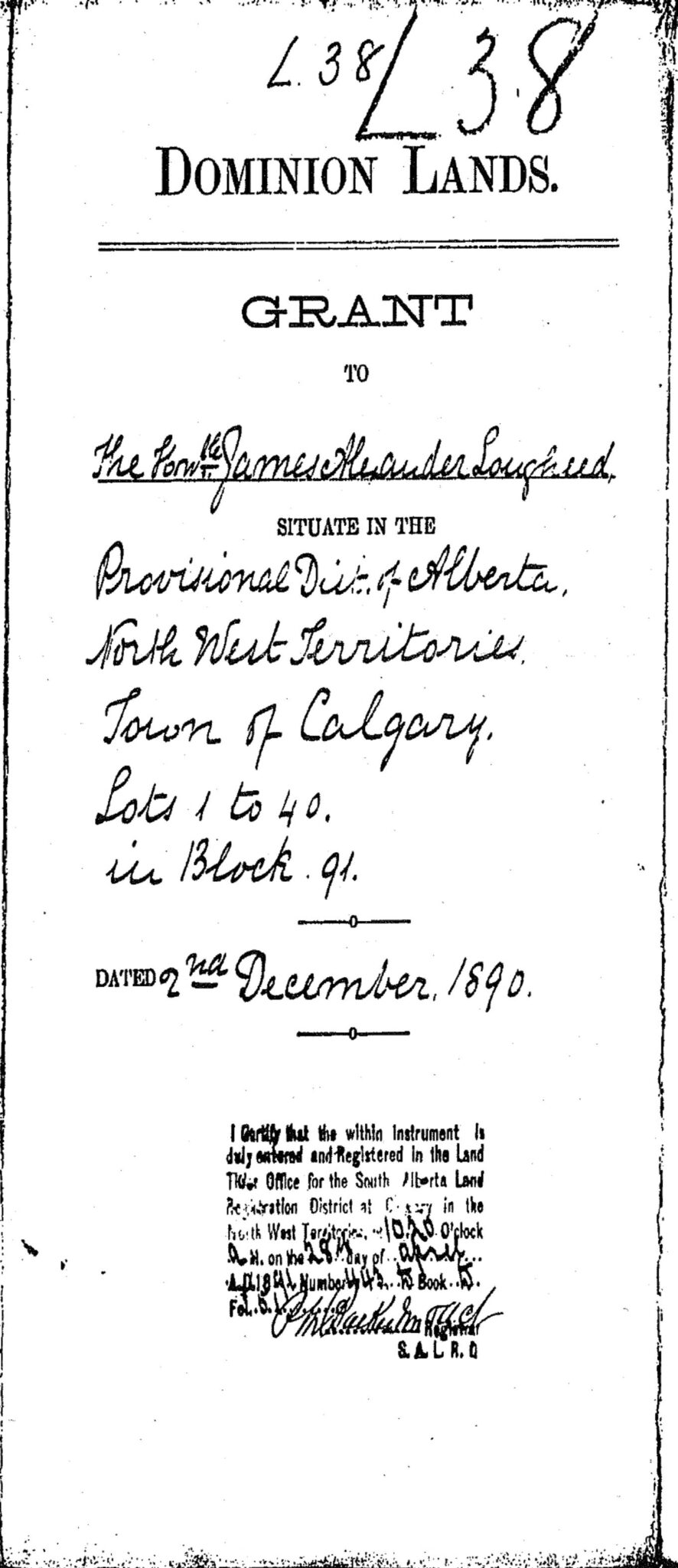

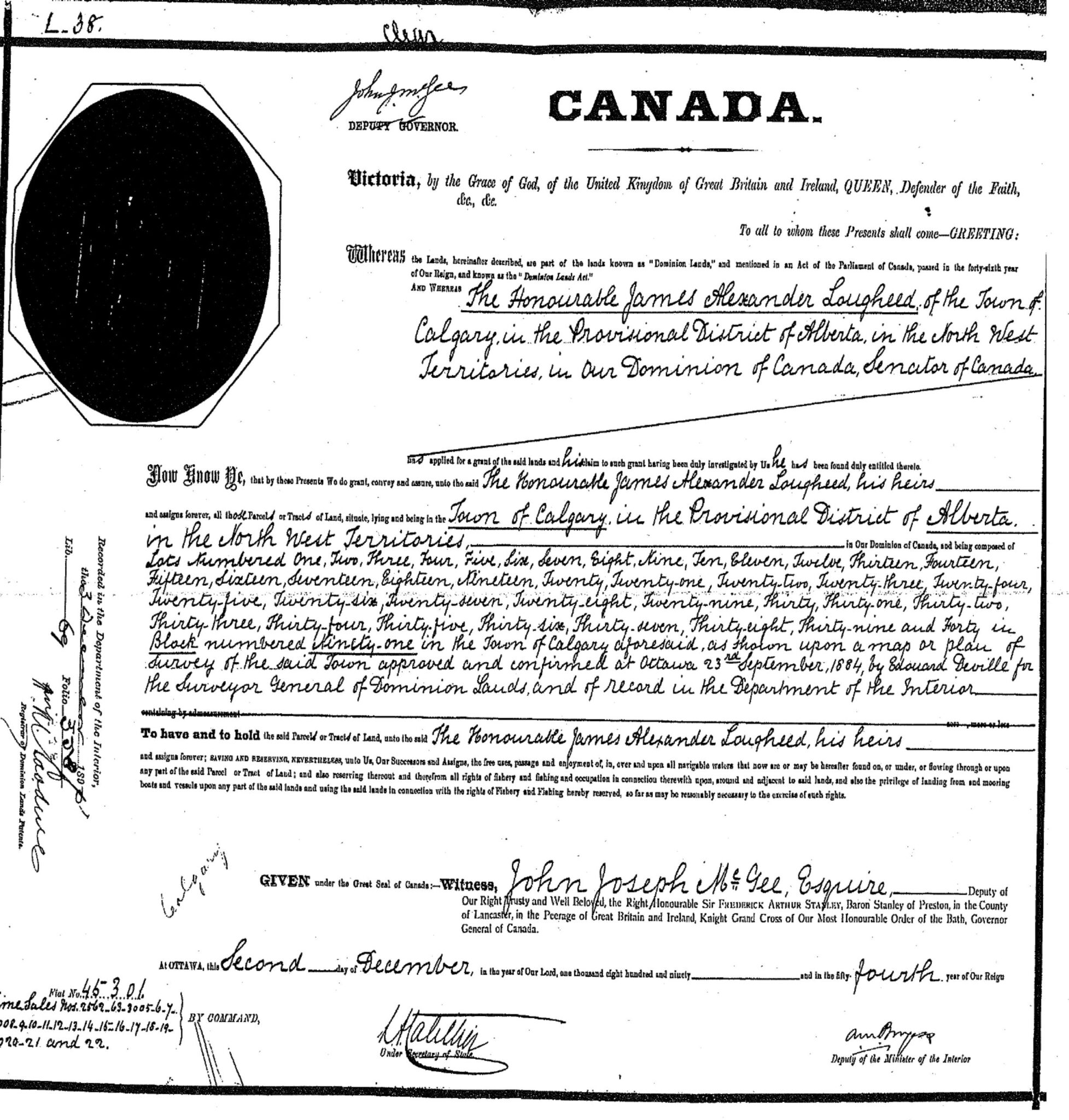

James bought and sold numerous lots and parcels of land through various avenues. Confirmed sources indicate he acquired land through the CPR, and there is some speculation that James may have benefited from a more controversial acquisition process through the manipulation of Métis scrip for land. Many of his contemporaries did acquire land this way, although we have been unable to confirm if James did in the archival record. [13] It appears that his acquisition of the lots for the house and grounds was achieved through a Dominion Lands Grant, as evidenced in the document dated 1890. Many questions remain unanswered about processes of land acquisition and ownership. It is a history that is muddied and controversial, and certainly a history that requires continual investigating and exploring in an attempt to find some sort of clarity to a very convoluted, often nepotistic and ruthless, imperialistic story. The question “This land is whose land?” is not a simple one.

James Lougheed’s Dominion Land Grant| December 2, 1890

James Lougheed’s Dominion Land Grant | December 2, 1890

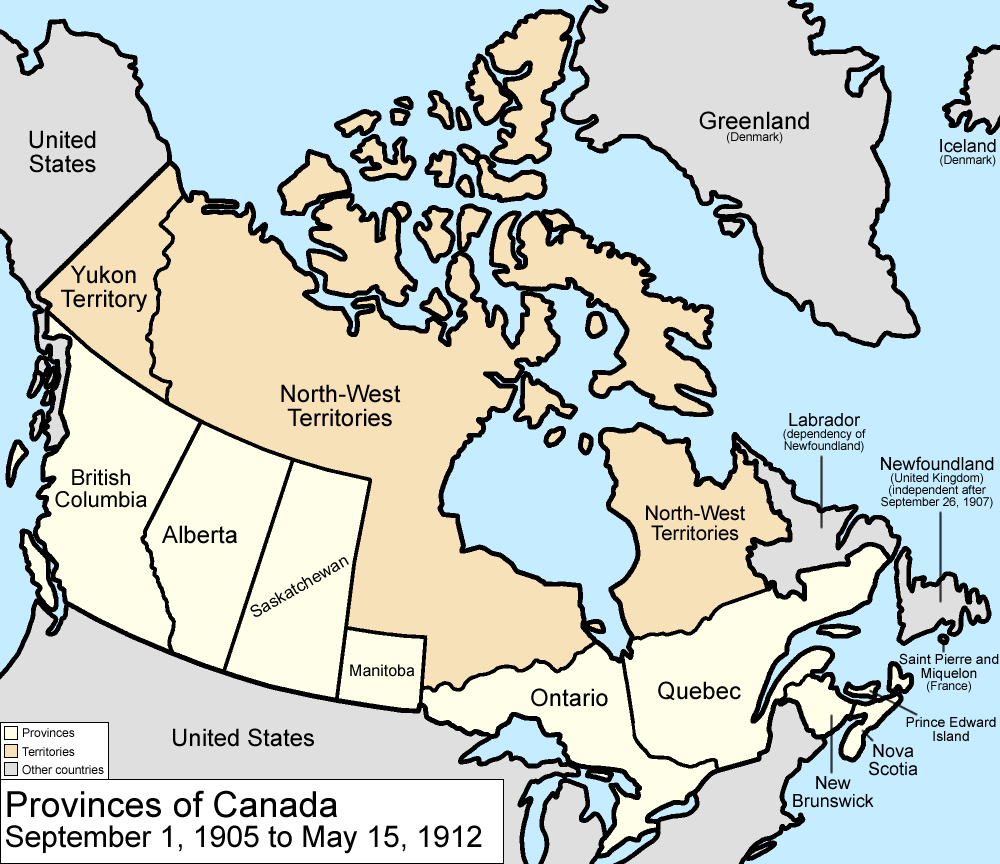

Canadian Provinces, 1905-1912

References

[1] History On This Day, May 2, 1670, “Charles II Grants Royal Charter to Hudson’s Bay Company”

[2] Hudson’s Bay Company History Foundation, Deed of Surrender

[3] Canadian Geographic, “The untold story of the Hudson’s Bay Company”

[5] The Canadian Encyclopedia, “Rupert’s Land”

[6] The Canadian Encyclopedia, “British Columbia and Confederation”

[7] Hudson’s Bay Company History Foundation, Deed of Surrender

[8] The Canadian Encyclopedia, “Dominion Lands Policy”

[9] For more information about the Royal Proclamation and some of its inherent issues check: https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/royal_proclamation_1763/ and https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/royal-proclamation-of-1763

[10] The Canadian Encyclopedia, “Royal Proclamation of 1763”

[11] Canadian History: Post-Confederation by John Douglas Belshaw, Chapter 2.9: The Railway

[12] McGill University, Canadian Pacific Railway

[13] Scrip is a certificate in lieu of legal tender that the bearer can use towards the purchase of a given item. In Western Canada, the government issued land scrip or money scrip to “Halfbreed heads of households” as well as Métis children between 1870 and 1921. The goal of Métis scrip was to provide the Métis people with a land base. The scrip system is widely regarded to have been a failure, resulting in the widespread dispossession of many Métis. This was because many non-Indigenous scrip speculators defrauded the Métis by obtaining the scrip and the underlying lands for their own benefit. This was a complex issue, even for the Hardisty/Lougheed family. Many members of the Hardisty family applied for and received scrip. As Leader of the Government in the Senate, in 1921 Senator James Lougheed introduced an amendment to the criminal code on behalf of the Government, which stated that Métis people could not litigate in relation to scrip fraud if more than three years had elapsed since the issue of said scrip. This limitation period left many Métis without legal recourse for fraud claims in relation to scrip speculation.

We respect your privacy as per our Privacy Statement. We welcome your thoughtful and respectful comments, and your first name will appear with each submission. All comments will be moderated by Lougheed House before they appear on the site. We check for posts regularly and will respond as soon as we can. We do not guarantee that your comments will be published.

By submitting a comment, you accept that Lougheed House has the right to reproduce and publish that comment in whole or in part, in any form we choose. We do not endorse the opinions expressed in comments. Comments on this page are moderated according to our Submission Guidelines. Comments are welcome while open. We reserve the right to close comments at any time.