Racism and Resistance: Early Black History in Calgary and Alberta

This blog post is the second in a series that reference the formation of various communities and social groups within early Calgary. The first in the series can be found at: Early Calgary’s Chinese Community and Chinese Freemasons.

Written by Kay Burns

Hidden Histories

Black history in the prairies is not well known. It is missing from educational curricula and in the stories told about Alberta. The overarching narrative taught in schools and history books is that western pioneers were White, yet there is much more to the story that is little-known or untold.

“I grew up a young Black girl in Olds, Alta., without ever hearing the name Amber Valley. Amber Valley was the largest Black community ever to have existed west of Ontario. It was only an afternoon’s drive away from where I lived…. there were gaping holes in my knowledge about a significant Black history that — had I learned of it as a child — would have utterly transformed my sense of belonging on the Prairies. How does history like this go missing?”[1]

-Karina Vernon

“Our story was casually and precariously preserved – kept alive more by word of mouth amongst ourselves than by any canonical record or acknowledgement of our presence.”[2]

-Cheryl Foggo

Black communities were indeed present on the prairies. Communities such as Maidstone in Saskatchewan and Wildwood, Breton (Keystone), Campsie, and Amber Valley in Alberta were settled by Black immigrants in the early 1900s. Growing towns and cities such as Fort Macleod, Fort Saskatchewan, Lethbridge, Edmonton, and Calgary saw the arrival of Black families and individuals as early as the late nineteenth century. Individuals such as John Ware, Annie Saunders, and Daniel Lewis were important Black pioneers in the southern Alberta region and remain important historical figures in Alberta history.

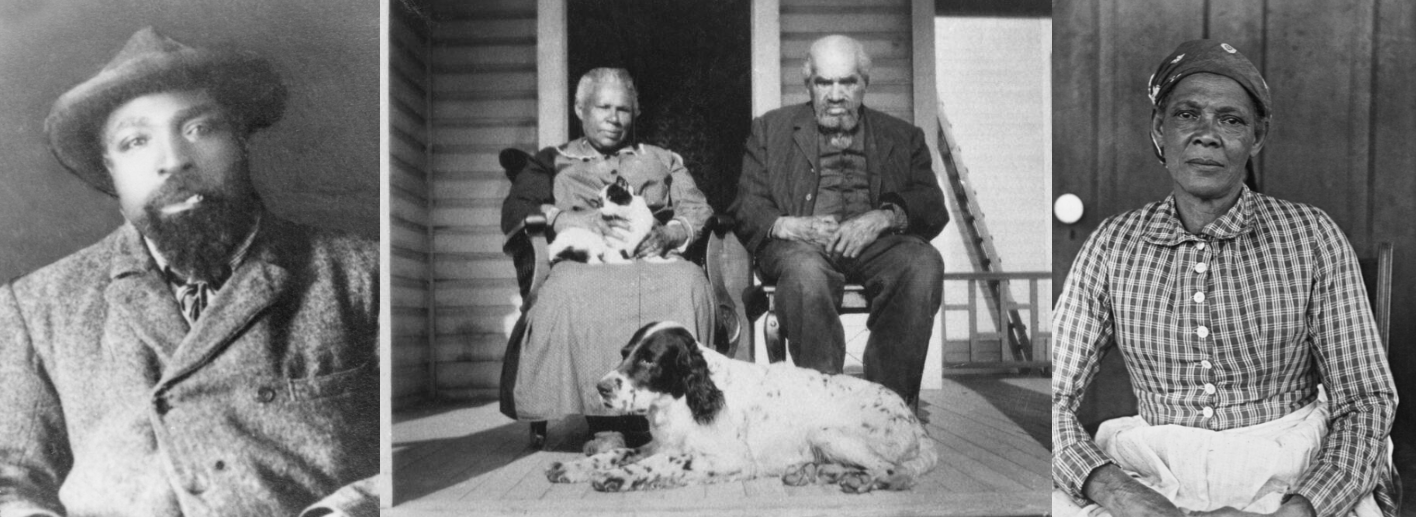

1. John Ware, one of “Alberta’s best-known cowboys and ranchers” arrived in 1882 as part of a team bringing in 3000 head of cattle to southwest Calgary and opened his own ranch in Millarville in 1900. | c. 1902-1903 | NA-101-37 | Glenbow Archives

2. Daniel Lewis, homesteader and carpenter, arrived with his family in 1889. His daughter, Mildred, married John Ware. Lewis’s mastery of carpentry led him to producing some of the railings and fine woodworking details in the homes of some of Calgary’s rich. Might it be possible that he participated in building the Lougheed home in 1891? | Charlotte Lewis and Daniel Lewis, Calgary, Alberta | c. 1915 | Unknown | PD-412-3-46 | Glenbow Archives

3. She was the nurse for Colonel James F. Macleod’s children. ‘Auntie’ was Annie Saunders. After leaving the employ of the Macleods, she ran a laundry, restaurant, and boarding home for children in Pincher Creek. | c. 1890 | E.M. Wilmot | NA-742-4 | Glenbow Archives

Part of the premise of Lougheed House Re-imagined is to examine and excavate hidden or unknown histories. Obscurant histories perpetuate racial misunderstandings, prejudice, and flawed interpretations of history. By exploring some of the lesser-known stories that have been veiled through colonial systems, new awareness and recognition can emerge.

Black Immigration

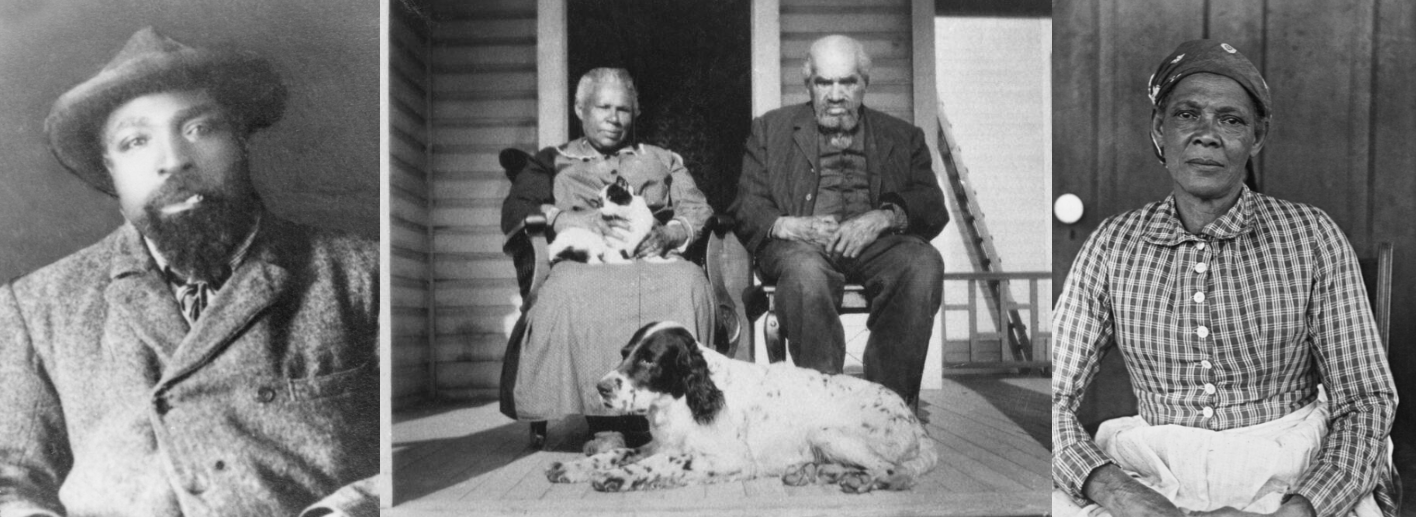

Following the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway, an aggressive federal government campaign (“Last Best West”, 1896-1914) was initiated to bring settlers to the prairie region, to enable agricultural industries to form in the newly accessible vastness known as Canada. The government’s plan entailed a recruitment approach that encouraged farmers from eastern Canada, Britain, and the United States to come for free land.

Poster advertising “The Last Best West” | The Globe, Toronto, via Wikimedia Commons

In the United States in 1907, the Oklahoma territory became a state. [3] Many Black people living there chose to leave Oklahoma to escape extreme racism that accompanied the enforcement of Jim Crow laws.[4] Canada and its land was an enticing prospect, and from 1908 to 1911 nearly a thousand Black people moved to Alberta.[5] This was seen as unacceptable by certain local organizations and community members, who actively complained and worked against the idea of Black settlers coming to Alberta and Calgary.

“The Canadian government would eventually attract more than a half million American farmers. What never occurred to Canadian officials was that Blacks, many of whom now looked to Canada as a favourable option, numbered among those farmers. The extensive promotional campaign with its exaggerated claims now had to be reversed where Blacks were concerned. How could the government explain that the western prairies would be great for white farmers but not for Black?”[6]

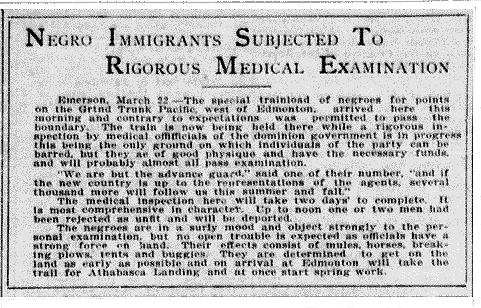

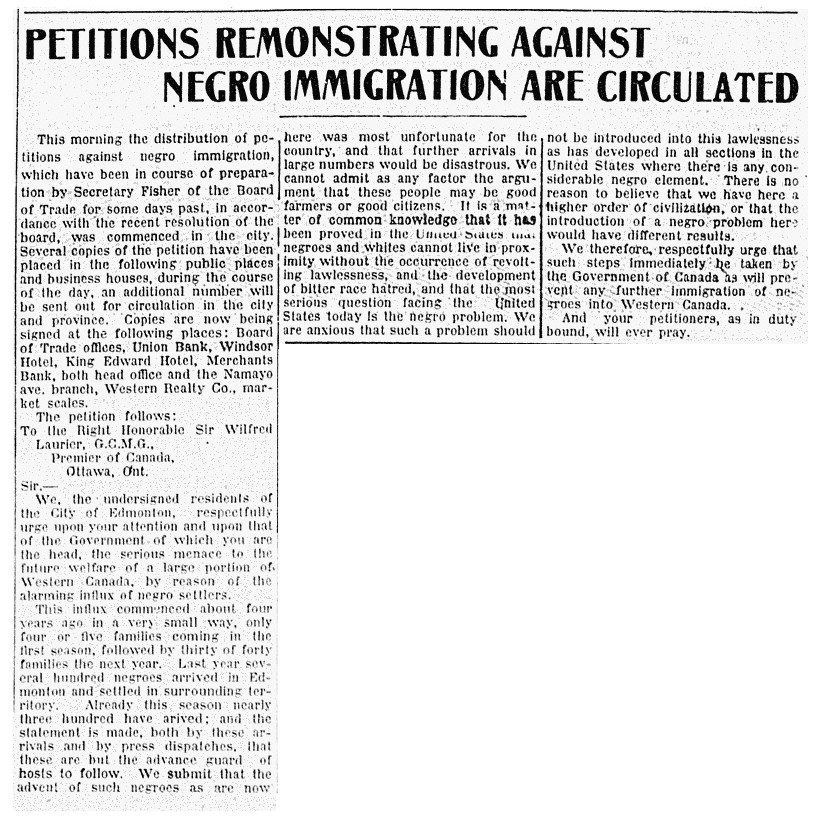

It wasn’t easy for newly arrived Black settlers: “They faced the challenge of not only taming a rough and unforgiving land, but as well encountered a harsh climate of intolerance…”[7] Vocal settler colonial residents complained of the increasing Black population in Alberta. The Board of Trade in Edmonton lobbied against Black immigration and “circulated a petition signed by roughly 3000 people and endorsed by the Morinville, Calgary, and Fort Saskatchewan Boards of Trade” which was sent to the Wilfred Laurier government in request to ban Black immigrants. [8] Other organizations in Alberta added fuel, such as the Imperial Order of Daughters of the Empire (IODE) who also wrote harsh letters “arguing that the ‘rapid influx of Negro settlers’ would bring property values down and discourage Whites from settling in the vicinity of Black farmers.”[9] In addition, the IODE and the United Farmers Association “sent petitions and letters citing black sexual impropriety and physical unsuitability as reason to bar black immigration.”[10]

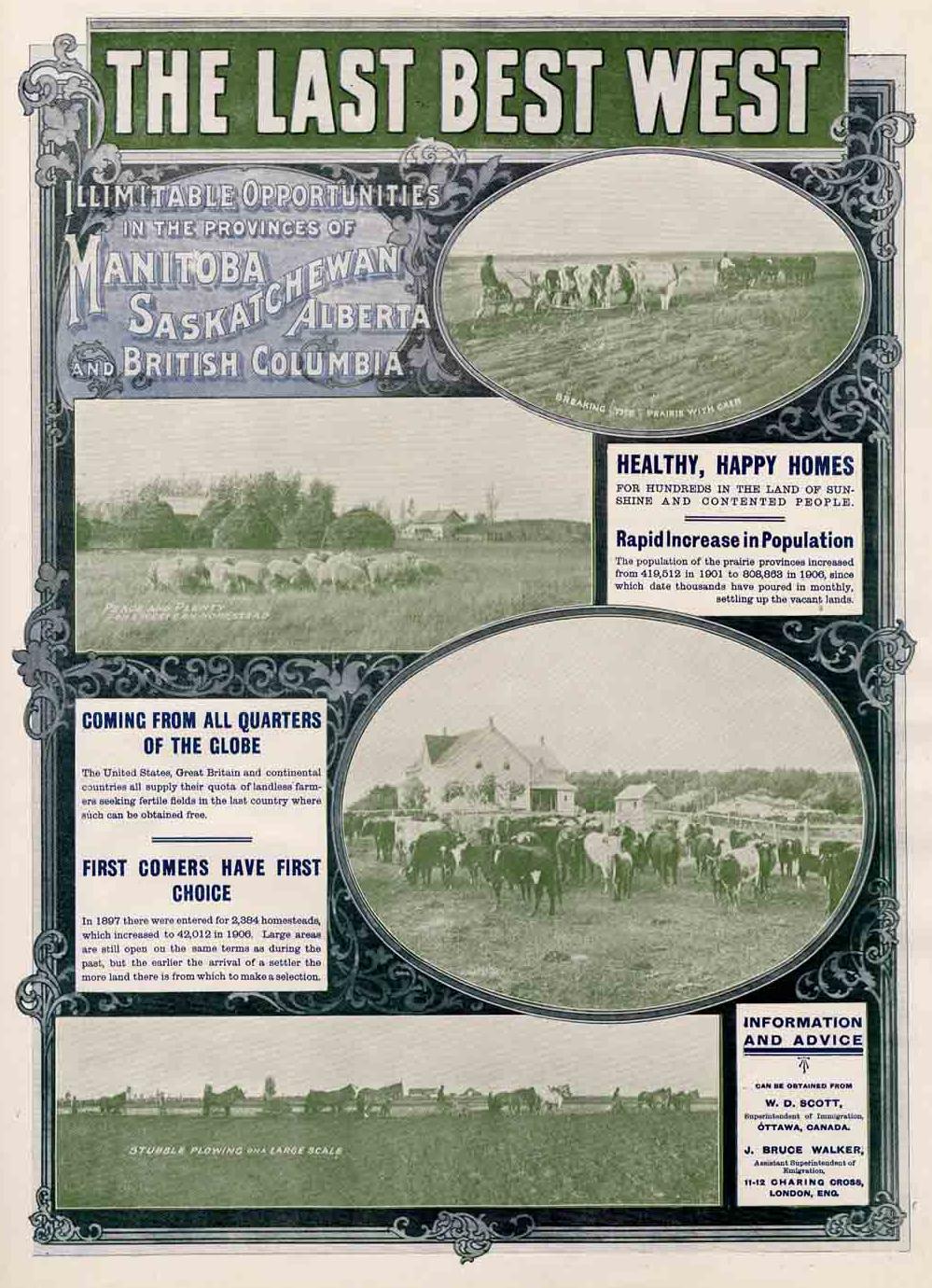

Prime Minister Wilfred Laurier approved an Order-in-Council that proposed to ban Black immigration for a one-year period in response to the petition and other complaints. The order did not pass into law, however, due to concerns of disrupting trade negotiations with the United States. [11] Instead, covert interventions took place both within the land promotions in the States and at the border. Government representatives were sent to the United States to discourage Black people from coming to Canada through stories of hardship, and the “Ministry of Immigration developed stringent medical exams, and doctors were offered bonuses for every Black they turned away at the Border.”[12]

“Negro immigrants subjected to rigorous medical examination.” | March 22, 1911 | Edmonton Bulletin

“Petitions Remonstrating Against Negro Immigration Are Circulated” | April 25, 1911 | Edmonton Capital

Social Organizations

Social groups were formed in Black communities during the early part of the twentieth century as “benevolent organizations designed to bring people together and help them to engage with politics, art, religion, and culture.”[15] Several were organized in Edmonton because it had the largest urban Black population in the prairies and was at the centre of several vibrant rural black communities located within a hundred miles of the city.[16] The Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), a worldwide organization started in Jamaica in 1914, was created to “further the human rights agenda through the promotion of racial uplift through Black agency.”[17] By the 1930s, fifteen UNIA branches opened in Canada, including branches in Edmonton and Calgary.[18]

A group called the Colored People’s Protective Association was present in early Calgary. Evidence of its activities exists within the local newspapers of the time. In October 1910, the association held a ball attended by a hundred and fifty people. The Calgary Herald wrote that it was “one of the most successful balls of the season” and that “many white people came to indulge in the festive spirit of the evening.”[19] An inverse situation of White settlers inviting or accepting Black community members into their own events was much less likely.

“The Colored Ball” | October 11, 1910 | Calgary Herald

However, it was not unusual for the dominant culture to toss nefarious accusations against Black community members. In 1912, an article in the Calgary News Telegram accuses the Colored Protective Association of supporting criminal activity. The journalist asks lawyer F. E. Eaton if the society was organized “for the purpose of practically promoting crime by the protection of criminals.”[20] Mr. Eaton responds by stating that the organization does provide funds to members who are prisoners and believed to be innocent, “But what is wrong with this? If a member of any other lodge is in trouble, don’t members of his order often come to his assistance by providing money for his defence? Yet none of these eminently respectable bodies would be accused of protecting criminals.”[21]

Resistance

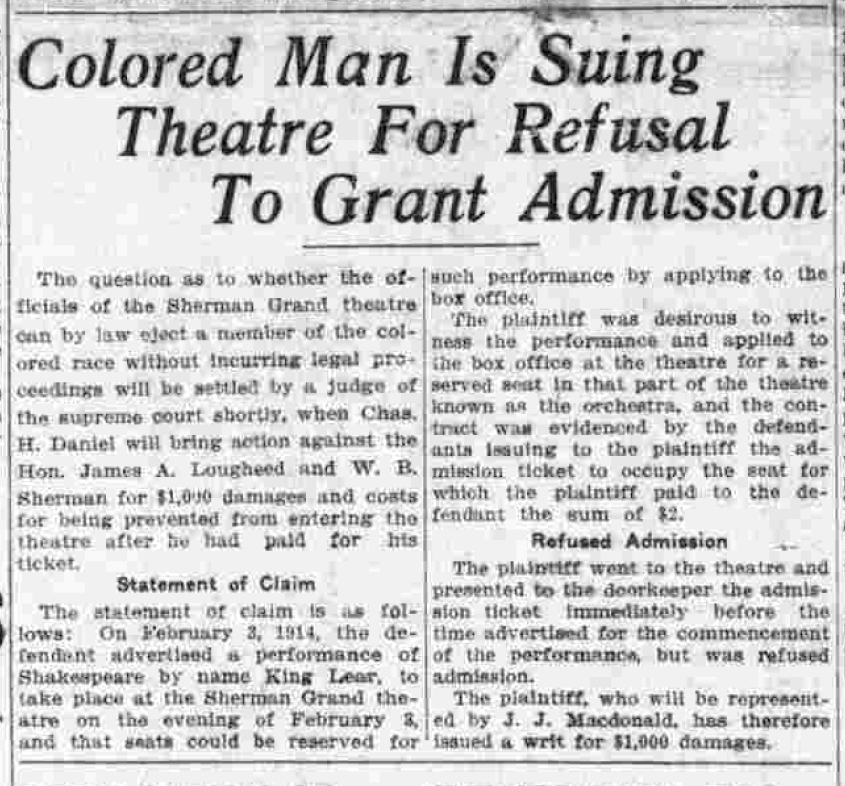

Social organizations emerged in resistance to discrimination that Black people encountered in Calgary. Individuals also acted in response to racism. In 1914, Charles Daniels, a Black man, arranged to purchase tickets to attend a performance of King Lear at the Grand Theatre. When he arrived, he was not permitted to sit in the seat allocated by his ticket and was told that instead he must sit in the “coloured” section. Shortly after this incident he brought a legal case against the theatre’s owner, James Lougheed, and the theatre manager, William Sherman.[22]

“Colored Man is Suing Theatre for Refusal to Grant Admission” | March 3, 1914 | Calgary Herald

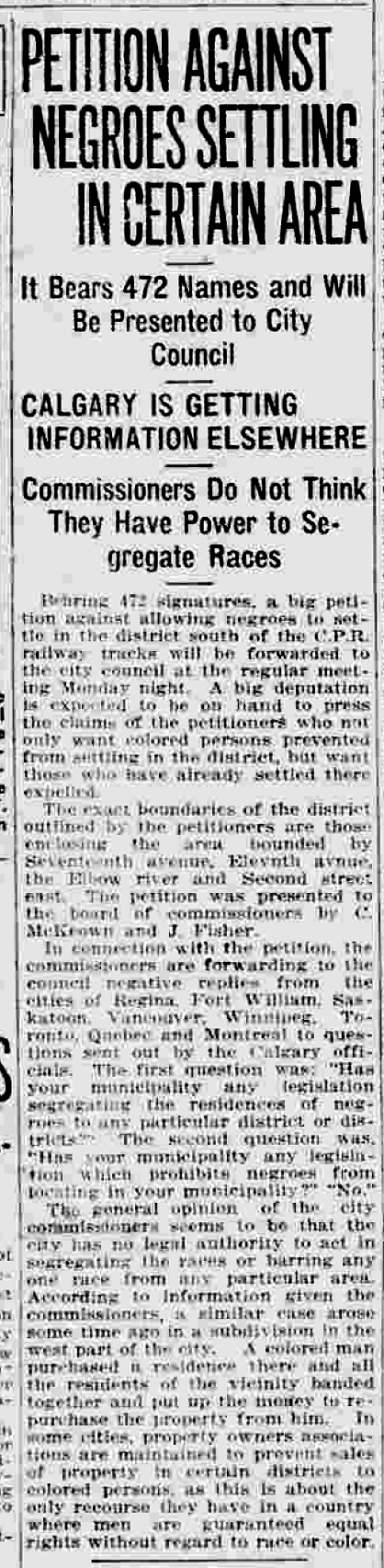

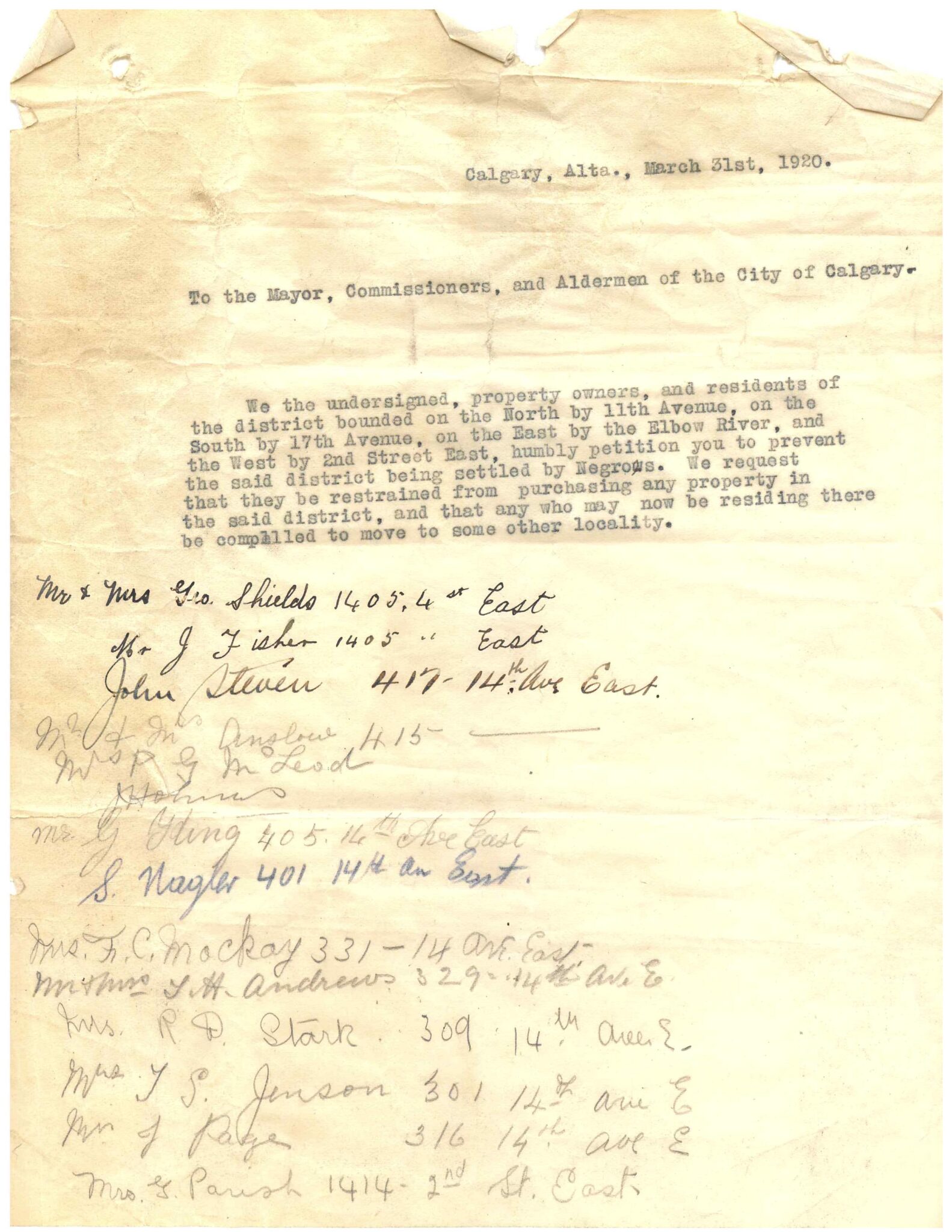

In 1920, a delegation of 472 White residents of Victoria Park, a community at the east end of the Beltline just a few blocks from the Lougheed home, brought a petition to City Council requesting that Black people not be allowed to buy homes in their neighbourhood and that those Black people who were already there be relocated elsewhere. [23] The City investigated the options and sought input from other cities across Canada, and found there was no precedent for banning or segregating Black citizens from communities. One alderman suggested they look to cities in the United States instead for precedents of segregation.[24] As there was no legal way for the petitioners to obtain their wishes, a committee was struck to try and reach an agreement. The committee included members of City Council, members of the petition delegation, and Black residents Mr. Stewart and Mr. Davis and their lawyer Mr. R.S. Burns. Mr. Burns pointed out that there could be no question whatsoever of the Black citizens’ legal rights to live where they chose, “but that they were willing to meet the white people who were objecting to their coming in a spirit of friendliness to discuss any settlement possible.”[25] While the Black residents living in Victoria Park had no plans to leave, the agreement entailed getting the Black residents to dissuade any further Black people from moving into the neighbourhood, even though they could not possibly be held responsible for strangers coming in. Calgary’s mayor, Robert Marshall, indicated “the most important point to be settled was that of preventing any more coloured people from moving into the disputed neighbourhood.” While he acknowledged that the “coloured deputation had accepted this suggestion,” he continued with the idea that “one of the best methods of preventing like trouble in the future was to get after real estate men who made such transfers.”[26] The so-called amicable settlement highlights the racist attitudes present within Calgary.

“Petition Against Negroes Settling in Certain Area” | April 26, 1920 | Calgary Herald

Page 1 of 14 page petition | 1920 | City of Calgary Archives, City Clerks Correspondence

Black residents living within the city encountered hostility as a regular part of their lives. Worker unions sought only White labour, and Black citizens were confronted with racism in many city businesses. Many Black men in Canada were employed as Sleeping Car Porters for the CPR from the late nineteenth century until the mid-twentieth century.[27] They faced discrimination in their roles and within the communities that were their home base. In Calgary, porters were often denied service in restaurants but found alternative places to meet: “They were welcomed by Chinese proprietors of a few cafes in particular in the 20s and 30s – the Chrystal Café and the Canadian Café, and the White owner of another – the Palace Café.”[28]

***

This blog only covers a few of the many circumstances and situations encountered by Black people in early Alberta; it demonstrates attitudes of White settler colonial systems and individuals within Calgary as it was growing. Black communities resisted and persisted; other social groups formed, and other activism occurred during the middle years of the twentieth century and beyond. For Lougheed House, as a museum with settler colonial origins, we are obligated to continue to unearth and concede stories of oppression, to acknowledge past inequities so that current systemic inequities can be recognized, revealed, and redressed.

Many thanks to Cheryl Foggo, a member of our Community Advisory Committee, for her review of the article.

Footnotes

[1] Karina Vernon, CBC Black on the Prairies, “I grew up a Black Girl in Alberta without ever hearing about Amber Valley. How does history go missing?” 2021.

[2] Cheryl Foggo, Directions: Research and Policy on Eliminating Racism, “My Home is over Jordan – Southern Alberta’s Black Pioneers,” Vol 4, No 1 Summer 2007, 46.

[3] Prior to becoming the State of Oklahoma, the region consisted of land inhabited by settlers from other parts of the US (including many freed slaves) called Oklahoma territory, as well as an area called “Indian Territory” that included lands of the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole peoples.

[4] https://humanities.utulsa.edu/oklahoma-home-historically-black-towns-u-s-state/ “Unfortunately, shortly after statehood in 1907, the Oklahoma State legislature passed a series of statutes that would come to be known as Jim Crow laws, essentially enforcing racial segregation and, in some cases, inciting racial violence. Many Americans became disheartened by this turn of events, and large numbers migrated to the west, as well as to Canada and Mexico.”

[5] David Este and Wek Mamer Kuol, “African Canadians in Alberta: Connecting the Past with the Present,” in David Divine, Ed., Multiple Lenses: Voices from the Diaspora Located in Canada, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle, UK, 2007, 32.

[6] Gwen Hooks, The Keystone Legacy: Reflections of a Black Pioneer, Brightest Pebble Publishing, 1997, 23.

[7] Este and Kuol, 31.

[8] Ibid., 33.

[9] The Fort Heritage Precinct, “Black History Month: Fort Saskatchewan and the 1911 Petition to Ban Black Immigration to Alberta”.

[10] Este and Kuol, 33.

[11] The Canadian Encyclopedia, “Order-in-Council P.C. 1911-1324 – the Proposed Ban on Black Immigration to Canada”.

[12] Este and Kuol, 33.

[13] Velma Carter, Windows of Our Memories, Vol II, St. Albert : Black Cultural Research Society of Alberta, 1990, 282.

[14] Ibid., 280.

[15] Carla Marano, “For the Freedom of the Black People: Case Studies on the Universal Negro Improvement Association in Canada, 1900-1950,” PhD thesis, University of Waterloo, 2018, 222.

[16] Ibid., 193.

[17] Teaching African Canadian History, “Forward Ever! Remembering and Teaching About Emancipation, Freedom, and Pan-Africanism in Canada”.

[18] Carla Marano, “Archival records, including a few interviews and written materials from the Provincial Archives of Alberta and the City of Edmonton Archives, provide insight into the lives of early black homesteaders in Alberta. In this way, these sources establish the historical context that helps to understand the appeal of the UNIA in western Canada. Regrettably, these documents offer no specific information on the UNIA divisions within the province of Alberta”, 194.

[19] Calgary Herald, “The Colored Ball,” October 11, 1910, 4.

[20] Calgary News Telegram, “Colored Protective Assoc’n Furnishes Funds to Prisoners,” June 17, 1912, 16.

[21] Ibid.

[22] A comprehensive overview of Charles Daniels’ activism can be found in Cheryl Foggo’s film Kicking Up a Fuss and Bashir Mohamad’s article, “Calgary’s Unknown Civil Rights Champion”.

[23] Jeremy Klaszus, Sprawlcast: Cheryl Foggo On Black Life in Alberta. The petition is in the archival records at City Hall; it was signed by approximately 75% of the community including future Prime Minister, R.B. Bennett [James Lougheed and R.B. Bennett were law partners from 1897-1922].

[24] Calgary Herald, “City Council lacks power to segregate coloured race,” Apr 27, 1920, 22.

[25] Calgary Herald, “Amicable settlement of race problem is possible,” Apr 29, 1920, 10.

[26] Calgary Herald, “Mixed committee suggested to settle racial problem.” Apr 30, 1920, 7.

[27] Travis Tomchuk, “Black sleeping car porters,” Canadian Museum for Human Rights.

[28] Cheryl Foggo, Directions: Research and Policy on Eliminating Racism, “My Home is over Jordan – Southern Alberta’s Black Pioneers,” Vol 4, No 1 Summer 2007, 49.

We respect your privacy as per our Privacy Statement. We welcome your thoughtful and respectful comments, and your first name will appear with each submission. All comments will be moderated by Lougheed House before they appear on the site. We check for posts regularly and will respond as soon as we can. We do not guarantee that your comments will be published.

By submitting a comment, you accept that Lougheed House has the right to reproduce and publish that comment in whole or in part, in any form we choose. We do not endorse the opinions expressed in comments. Comments on this page are moderated according to our Submission Guidelines. Comments are welcome while open. We reserve the right to close comments at any time.

So closely like that of people of African descent in the maritimes only we go back another 100 years.

This is my families history. We just discovered that our family was one of the original families in Campsie. Where can I find more information specifically on Campsie? Feel free to reach out.